Biography

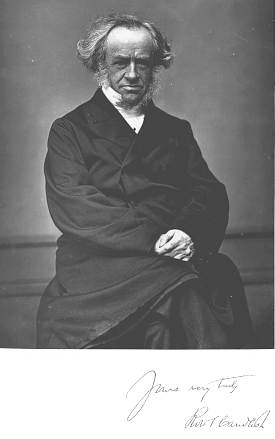

ROBERT SMITH CANDLISH was born at Edinburgh on the 23d of March 1806,

being the youngest child of James Candlish, a teacher of medicine there. His

mother was Jane Smith, one of the six "Mauchline

belles" celebrated by Robert Burns, who said of her, "Miss Smith she has

wit" His father, whose surname was originally M'Candlish, but who dropped the

Celtic prefix when at Glasgow College, was also a friend of the poet. He died

very suddenly, a few weeks after his son Robert was born, April 29, 1806; and

thereupon his widow with her family, consisting of two sons and two daughters,

removed to Glasgow, where they continued to reside for many years. There,

accordingly, Robert Candlish spent his early days. He was at first a somewhat

delicate and rather timid boy, but soon getting over this, he joined with

hearty enjoyment in the games and amusements of his companions. He entered

Glasgow College, 10th October 1818, at the early age of twelve; and attended

the gown or undergraduate classes for five sessions, during which be gained

many prizes, and in due time took the degree of MA.(See article "influences").

At this time

Dr. Chalmers was minister of

St. John's church and parish, and had as his assistant Edward Irving, whose

great gifts as a preacher were not then generally appreciated. The church was

crowded when Dr. Chalmers preached, but comparatively empty when his assistant

was to occupy the pulpit. Robert Candlish, however, with a few friends and

fellow-students, while fully appreciating the eloquence of Dr. Chalmers,

enjoyed almost as much the services of his then unpopular assistant, and was

one of his regular hearers. In 1823 he entered the Divinity Hall of the Church

of Scotland, which he attended during three regular sessions, completing the

course required by the Church by one partial session, and finally leaving

college in December 1826.

The Professor of Divinity in those days was

Dr. Stevenson MacGill, a man of earnest piety and decidedly evangelical

opinions, who contributed much, by his quiet influence, to the spread of sound

doctrine and the advance of spiritual life among the ministers of the Scottish

Church. During a great part of his college course Robert Candlish was largely

employed in private teaching, sometimes as much as eight or ten hours a day, in

addition to his studies. In 1826 he went with Sir Hugh Hume-Campbell, as

private tutor, to Eton College, where he remained till 1829, thus getting an

opportunity of seeing some thing of English school and church life. Meanwhile,

when at home during one of his vacations, he was licensed as a preacher of the

gospel by the Presbytery of Glasgow, August 6, 1828; and on returning to reside

in Glasgow in 1829 he was engaged as assistant by Dr. Gavin Gibb, the minister

of St. Andrew's, in that city. Though

not yet ordained as a minister, he had the entire charge of the congregation,

as well as the whole supply of the pulpit; and he preached regularly twice

every Sabbath, only occasionally exchanging services with other ministers. In

this capacity, while almost entirely unknown, he prepared and delivered, in the

ordinary course of his duty, some of those sermons that afterwards made a

profound impression in St. George's, Edinburgh, and established his fame as a

preacher. He enjoyed at this time the companionship and friendship of the Rev.

David Welsh, then minister of St. David's, who early appreciated his gifts, and

frequently invited him to preach to his own congregation. This friendship

continued warm and unbroken till the too early death of Dr. Welsh in 1845. With

Dr. Srnyth of St. George's, Dr. Henderson of St. Enoch's, and Dr. Robert

Buchanan of the Tron Church, he also formed early, and life-long

friendships.

During these years, domestic sorrow had visited the home of

the young preacher. One of his sisters had died in 1827, and his only brother,

James Smith Candlish, a young man of great gifts, and much beloved by his

relatives and friends, was cut off, just as he was entering a most promising

career in the medical profession, and had been appointed Professor of Surgery

in the Andersonian University. He died of fever, September 15, 1829.

On

the death of Dr. Gibb in June 1831, Mr. Candlish's engagement in

St. Andrew's came to an end, and

thereafter he became assistant to Mr. Gregor, the minister of the country

parish of Bonhill, in the vale of Leven, Dumbartonshire. Here, too, the whole

of the pulpit and pastoral duties were entrusted to him, and he discharged them

with such zeal and diligence as to endear himself to the hearts of the people.

In this position he remained for two years and three months. But though he had

been thus long engaged in full ministerial work; he was still little known

beyond a small circle as an able and evangelical preacher, and seemed as far as

ever from obtaining, then the utmost aim of his ambition, some small country

charge as ordained minister. So little prospect did there seem of this, that he

seriously contemplated going out to the colonies, and actually offered himself

for work in Canada. But the great Head of the Church had another position

preparing for him.

The congregation of St. George's, Edinburgh, had been

raised to the highest position in that city by the zeal and eloquence of

Dr. Andrew Thomson, who was

suddenly cut off in 1831. It was soon after deprived of the services of his

saintly successor Mr. Martin, by the state of his health, which required a

residence in Italy. His place was supplied by assistants; and in January 1834,

Mr. Candlish succeeded his friend Mr. Roxburgh (now Dr. Roxburgh, of Free St.

John's, Glasgow) in this capacity. When Mr. Martin's ill health was found to

continue, and it became necessary to have an ordained assistant and successor,

the young preacher from the West had so proved his gifts, and gained the hearts

of the flock, that he was chosen to this office but Mr. Martin having died in

Italy in the following May, Robert Smith Candlish was ordained to the entire

charge of the congregation on the 14th of August.

In the summer of 1833

he had preached on four Sabbaths in the National Scotch Church, Regent Square,

London, then vacant by the removal of Edward Irving; and had made so favourable

an impression that the session and congregation desired earnestly to have him

as their minister. They were, however, not in a position to give him any

invitation to London till the spring of the next year, by which time steps had

begun to be taken towards his settlement in St. George's. Though he accepted

this as the prior call; the circumstance now mentioned led to a warm and

lasting friendship between Dr. Candlish and some of the elders of Regent Square

Church; and was the first, though not the last, link that connected him with

that congregation.

The new ministry in St. George's was thoroughly

efficient. Not only was the power of the pulpit fully maintained, but pastoral

visitation and works of Christian beneficence were zealously and diligently

conducted; and the members of the congregation set to working for the cause of

Christ. One result of these labours was the formation of the congregation of

St. Luke's, out of a section of St. George's parish, the first of a series of

efforts in Home Mission and Church extension that the congregation successfully

made.

But the even tenor of this course of Christian usefulness was

somewhat broken, though never interrupted, by the troubles of the Church of

Scotland, which called the minister of St. George's to take an active part in

the conflict she was then waging for her rights and liberties. He was a member

of General Assembly in 1839, when the House of Lords had just given the final

decision on the first Auchterarder case, denying

the legality of the Veto Act of 1834, by which the Church had sought to secure

the freedom of her people in the purely spiritual matter of the calling and

ordination of ministers over them. The Moderate party proposed that that Act

should, without being repealed by the Church, be thenceforth disregarded, since

it had been declared illegal by the supreme civil tribunals of the country. In

the debate on this point, Mr. Candlish made his first

Assembly speech. It was in support of the view

that, as the Veto Law was not of a civil nature, it could not be given up by

the Church in deference to the Civil Courts, without surrendering her spiritual

independence as a Church of Christ; and it was more especially called forth by

a motion made by Dr. Muir, attempting a sort of middle course or compromise

between the two opposing principles. "The objections to the scheme were

stated," says Dr. Buchanan, "and urged with singular felicity and force, by one

who was destined from that day for ward to exert perhaps a greater influence

than any other single individual in the Church, upon the conduct and issue of

this eventful controversy.

The reputation of Mr. Candlish as a preacher

was already well known. His extraordinary talents in debate and his rare

capacity for business, not hitherto having had any adequate occasion to call

them forth, were as yet undiscovered by the public, probably undiscovered even

by himself. They seemed, however, to have needed no process of training to

bring them to maturity. The very first effort found him abreast of the most

practised and powerful orators, and as much at home in the management of

affairs as those who had made this the study of their life. There was a

glorious battle to fight, and a great work to do on the arena of the Church of

Scotland; and in him, as well as in others evidently raised up for the

emergency, the Lord had his fitting instruments prepared. Mr. Candlish's powers

in debate and in the conduct of business led to his having some of the most

important public duties in the Church entrusted to him, as new and greater

complications arose; especially from the course pursued by the Presbytery of

Strathbogie, in the Marnoch case. The majority of that Church Court resolved,

in disobedience to the express injunctions of their ecclesiastical superiors,

and in deference to the Civil Court, to ordain to the charge of the parish of

Marnoch a man, against whom the whole congregation solemnly protested; and it

became necessary to suspend them from their office, not as a punishment, but

simply to prevent their committing this gross outrage in the name of the

Church. A special meeting of the Commission of Assembly was held in December

1839, at which Mr. Candlish moved, and carried by a majority of 121 to 14, the

suspension of seven ministers of the Presbytery of Strathbogie. Immediately

thereupon he had to go down to that district, along with Mr. Cunningham and

others, to intimate in the parishes of the several suspended ministers the

sentence that had just been pronounced. But before this could be done, these

ministers had obtained an interdict from the Court of Session against the

sentence being intimated in their parish churches, churchyards, or schools.

This interdict, though it was held to be unjust and oppressive, was without

hesitation obeyed; because it related only to the use of premises which were

the property of the State, and so within the jurisdiction of the Civil

Court.

Accordingly, it was in the open air that Mr. Candlish preached at

Huntly, and other ministers in the other parishes, intimating the suspension of

the ministers, and supplying ordinances to their people. Soon afterwards,

however, the Court of Session, on the application of these ministers, granted

an extended interdict, forbidding any ministers of the Established Church to

preach anywhere within these parishes without the authority of the legal

incumbents. As this interdict interfered directly with the purely spiritual

function of preaching the gospel, it was deliberately disregarded; and the most

grave and godly ministers of the Church willingly went, at her appointment, to

dispense the means of grace among the people whose ministers had been

suspended. Mr. Candlish was not sent on this duty till the spring of 1841, when

he again preached in Huntly, this time in a new place of worship that had been

built by voluntary contributions. This act, though it was in no way different

from what the evangelical ministers of the Church of Scotland had been

systematically doing for a year past, was made the occasion of depriving him of

an appointment for which he was highly qualified.

By the recommendation

of a Royal Commission, the Government had resolved to institute a Chair of

Biblical Criticism in the University of Edinburgh; and Mr. Candlish was

nominated as its first occupant. The appointment was all but completed, when

Lord Aberdeen made a violent attack upon him in the House of Lords, alleging

that he had violated the law by preaching at Huntly about a fortnight before;

and, in consequence of this, Lord Normanby, the Home Secretary, cancelled the

appointment. In his published letter to Lord Normanby on this subject, which at

the time made a deep impression, Mr. Candlish vindicated himself from the

charge of breaking the law, and pointed out the deep-rooted convictions and

high principles that were involved in the unhappy conflict between the Church

and the Civil Courts.

In the Assembly that followed, he melted and

almost carried away the whole house by his persuasive and pathetic appeal to

the Moderate party to acquiesce in the passing of the Duke of Argyll's Bill,

which would have put an end to the conflict. This and other attempts at an

adjustment proved vain; and matters went on into further complications; till at

length, the House of Lords, having finally decided the claim of the Church to

spiritual freedom to be illegal, and the Ministry and Parliament having

declined to give any relief, the ministers who supported that claim, 474 in

number, among whom was Dr. Candlish, separated from

the State, and resigned their livings in connection with

the Scottish Establishment in May 1843.

In the various discussions and

negotiations that preceded this event, as well as in the labours needed for

building up the Church in her disestablished state, Dr. Candlish (who had

received the degree of D.D. from Princeton College, New Jersey, in 1841) took

an active and leading part.

He made numerous journeys, both in Scotland

and England, advocating the principles of the Free Church, and extending her

organisation. He took charge, at different times, of various of the schemes of

the Church, more especially of that for Education, having been convener of that

committee from 1846 to 1863. Yet, in the midst of all this public activity, he

kept up his pulpit and pastoral work, and attached more and more closely to him

the large and intelligent congregation of St. George's. During the Assembly of

1847, the sudden and lamented death of Dr. Chalmers created a vacancy in one of

the chairs of Theology in the New College; and in August that year Dr. Candlish

was appointed Professor by the Commission of Assembly. As he had ever a strong

conviction of the superior importance of the training of the Church's future

ministers, compared with the pastorate of any one congregation; he accepted the

appointment, and preached a farewell sermon to the people of St. George's. But

on this occasion, as on the former one, he was providentially hindered from

exchanging the work of the pastorate for that of the college. The congregation

of St. George's, with one heart and voice, had chosen as his successor the

gifted and pious Alexander Stewart of Cromarty; but before he could be inducted

into the charge, his sensitive nature had given way under the strain and burden

of the prospect, and he died November 5, 1847.

This sudden stroke made a

deep impression on the congregation and on Dr. Candlish, who, feeling that his

heart was too much with his afflicted people to give himself wholly to the work

of his chair, requested, and was allowed by the College Committee, to continue

the charge of St. George's during the winter, meeting the students only once a

week for the study of Butler's Analogy. At next Assembly, having been led to

think that his call to the professorial office was not so strong as he had

supposed, he formally resigned the chair, and was restored to the ministry of

St. George's.

He continued to lead his people in active Christian work;

and besides the home mission work that was constantly carried on in the

original parish of St. George's, the territorial missionary congregations of

Fountainbridge (out of which grew the Barclay and Viewforth churches) and

Roseburn, were originated, and fostered into strength and vigour, under his

care. His labours in the general administration of the Church's business it is

not possible even to enumerate here, much less to describe. He always took a

peculiar and warm, interest in the more directly spiritual part of the Church's

work, such as the promotion of vital religion, evangelistic labours in our own

country, and missions to the Jews and heathen abroad.

Nor was he inactive

in the field of literature, edifying the Church of Christ by his popular and

practical works, and, when necessary, defending in controversy her fundamental

doctrines. In 1842 he published the first volume of his "Contributions towards

the exposition of the Book of Genesis," afterwards completed in three volumes.

In 1845 an incidental newspaper correspondence called forth from him a small

volume "On the Atonement," which was recast and enlarged in 1861. In 1854,

being invited to lecture to the London Young Men's Christian Association in

Exeter Hall, he took the occasion to review the teaching of the Rev. F. D.

Maurice, in his "Theological Essays," then just published; and he issued along

with his lecture a detailed "Examination" of that work. But the accumulated

toils of what was virtually three lives in one - that of a city minister, of a

church leader, and of a theological writer - told upon his constitution; and,

in the spring of 1860, Dr. Candlish had a severe illness, by which he was laid

aside for several months. In the following year, he consented, to the proposal

of his congregation to have the help of a colleague; and the Rev. J. 0. Dykes

was inducted in that capacity, December 19, 1861, and continued to fill the

office till 1865, when he resigned his charge on account of ill

health.

In 1861 Dr. Candlish occupied the chair of the General Assembly;

and in the following year he was appointed Principal of the New College,

Edinburgh, in the room of Dr. Cunningham, who died December 14, 1861.

As

head of the College he opened and closed each session with an address to the

students; and heard and criticised the popular sermons which they are required

to deliver. When the Cunningham Lectureship was founded, Principal Candlish was

appointed the first lecturer, and delivered his course on the "Fatherhood of

God" in February and March 1864. The views therein expressed he had long held

and indicated in many of his sermons, such as those printed in the Appendix to

the Lectures, and in his subsequent volume "On the Sonship and Brotherhood of

Believers." But they appeared new, and even dangerous, to certain zealous

defenders of orthodoxy; and gave rise to a somewhat keen

controversy.

Dr. Candlish's Lectures on the First Epistle of John,

whicti were written and preached before the delivery of the Cunningham

Lectures, though not published till 1866, form, as it were, a Biblical

illustration and practical application of them.

Meanwhile his health was

becoming ever more broken and uncertain - his attacks of illness were more

frequent and severe; though his zeal and devotedness to the cause of Christ and

his Church never flagged. He was more especially active and earnest in the

negotiations for union among the unestablished Presbyterian churches in

Scotland, which were carried on from 1863 to 1873; though unhappily without

attaining the great object aimed at. In 1871-2 he was laid aside from all work,

for eleven months by a severe and exhausting illness; but, in the winter of

1872-3, he was permitted again to occupy his pulpit, and preached to his

beloved people on most of the Sabbaths of that season. The burden, however, of

the congregational work had been necessarily devolved on the Rev. A. Whyte,

who, since his induction as colleague in October 1870, had in every way

consulted for his comfort and relief, and in whom he placed the utmost

confidence. In the weeks preceding the Assembly his strength was much reduced,

and the effort that he then made to take part in its proceedings was a great

strain upon him.

He preached only twice after it - for the last time on

the 15th of June. The three following months he spent at Whitby, returning to

Edinburgh in the end of September. The decline of his strength now became more

rapid; and from the 10th of October his medical advisers began to fear that he

would not rally. When they told him their opinion, he fully realised and calmly

faced the prospect before him; and it made no change whatever upon him. He gave

his last directions with his wonted exactness, and with perfect composure; he

was cheerful and happy, and took an interest in passing events to the last; he

was affectionately mindful of all his friends, present and absent, and bade a

loving farewell to those of them whom he was able to see.

He delighted

to hear his favourite texts and hymns, those most full of Christ; and without

either great exaltation or depression, but "knowing whom he had believed," he

calmly waited the end, and peacefully fell asleep just before midnight on

Sabbath, October 19th.

From first to last it has taken from various

periods of his ministry, from its beginning in St. Andrew's, Glasgow, to its

close, that all will witness to his fidelity to the resolution to know nothing

among his people but Jesus Christ and him crucified. *

Many of the places mentioned above can be viewed by proceeding to the Chalmers site, photo-wallet.

Home | Biography | Literature | Links | Letters | Photo-Wallet